History

Ancient Iran, also known as Persia, historic region of southwestern Asia that is only roughly coterminous with modern Iran. The term Persia was used for centuries, chiefly in the West, to designate those regions where Persian language and culture predominated, but it more correctly refers to a region of southern Iran formerly known as Persis, alternatively as Pārs or Parsa, modern Fārs. Parsa was the name of an Indo European nomadic people who migrated into the region about 1000 BC. The first mention of Parsa occurs in the annals of Shalmanesar II, an Assyrian king, in 844 BC. During the rule of the Persian Achaemenian dynasty (559–330 BC), the ancient Greeks first encountered the inhabitants of Persis on the Iranian plateau, when the Achaemenids—natives of Persis—were expanding their political sphere. The Achaemenids were the dominant dynasty during Greek history until the time of Alexander the Great, and the use of the name Persia was gradually extended by the Greeks and other peoples to apply to the whole Iranian plateau. This tendency was reinforced with the rise of the Sāsānian dynasty, also native to Persis, whose culture dominated the Iranian plateau until the 7th century AD. The people of this area have traditionally referred to the region as Iran, “Land of the Aryans,” and in 1935 the government of Iran requested that the name Iran be used in lieu of Persia. The two terms, however, are often used interchangeably when referring to periods preceding the 20th century.

List of Iranian dynasties

Median: 728–549 BCE

Achaemenian: 559–330 BCE

Macedonian Empire and the Seleucids: 330–247 BCE

Parthian perio: 247 BCE–224 CE

Sasanian: 224–651

Arab invasion, Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate: 640–829

Samanid Empire: 819–999

Saffarid Kingdom: 861–1003

Ziyarid Kingdom: 928–1043

Buyid Kingdom: 934–1062

Ghaznavids Empire: 977–1186

Seljuqs 1029–1194

Khwarazmian Empire 1153–1220

Mongols and Ilkhanate: 1220–1335

Sarbadars, Chobanids, Jalayirids, Injuids and Muzaffarids: 1314–1393

Timurids: 1380– 1467

Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu: 1375–1503

Safavid: 1501–1736 , 1732-1736

Afghan interlude: 1723–30

Afsharid:1730–50

Zand: 1751–94

Qajars: 1794–1925

Pahlavi: 1925–79

Islamic republic: Since 1979

Medes

The accounts relating to the Medes reported by Herodotus have left the image of a powerful person, who would have formed an empire at the beginning of the 7th century BC that lasted until the 550s BC, played a determining role in the fall of the Assyrian Empire and competed with the powerful kingdoms of Lydia and Babylonia. it appears that after the fall of the last Median king against Cyrus the Great of the Persian Empire, Media became a crucial province and was rewarded by the empires, which successively dominated Achaemenid, Seleucids, Parthians and Sasanids. The Median empire, according to Herodotus, a dynasty composed of four kings who ruled for 150 years under the Median Empire. If Herodotus’ story is true, the Medes were unified by a man named Deioces, the first of the four kings who would rule the Medan Empire, a mighty empire that included large parts of Iran and eastern Anatolia.

Ecbatana in Hamedan

Achaemenian Dynasty

After the death of Cambyses II (522 BCE) the junior line came to the throne with Darius I. Probably the greatest of the Achaemenian rulers were Cyrus II (reigned 559– 529 BCE), who actually established the empire and from whose reign is dated; Darius I (522–486 BCE), who excelled as an administrator and secured the borders from external threats; and Xerxes I (486–465 BCE), who completed many of the buildings begun by Darius. During the time of Darius I and Xerxes I, the empire extended as far west as Macedonia and Libya and as far east as the Hyphasis (Beās) River; it stretched to the Caucasus Mountains and the Aral Sea in the north and to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Desert in the south. The dynasty became extinct with the death of Darius III, following his defeat (330 BCE) by Alexander the Great.

Bas-relief of Darius in Persepolis

Alexander conquest and Seleucid Empire

From 334 to 331 BCE, Alexander the Great, defeated Darius III in the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela. Between 334 and 330 BC Alexander completed the conquest of the whole Achaemenian Empire. Alexander’s burning of the royal palace at Persepolis in 330 symbolized the passing of the old order and the introduction of Greek civilization into western Asia. Greek and Macedonian soldiers settled in large numbers in Mesopotamia and Iran. Alexander left no heir. His death in 323 BC signaled the beginning of a period of prolonged internecine warfare among the Macedonian generals for control of his enormous empire. Alexander’s empire broke up shortly after his death, and Alexander’s general, Seleucus I, tried to take control of Iran, Mesopotamia, and later Syria and Anatolia. His empire was the Seleucid Empire. He was killed in 281 BCE.

Alexander Mosaic, showing Alexander fighting king Darius III of Persia in the Battle of Issus. Pompeii

Parthian

The first ruler of the Parthians and founder of the Parthian empire was Arsaces I, By 200 BC Arsaces’ successors were firmly established along the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. Later, through the conquests of Mithradates I (reigned 171–138 BC) and Artabanus II (reigned 128–124 BC), all of the Iranian Plateau and the Tigris-Euphrates valley came under Parthian control. Mithradates II the Great (reigned 123–88 BC), by defeating the Scythians, restored for a while the power of the Arsacids. In 92 BC Mithradates II, whose forces were advancing into north Syria against the declining Seleucids, concluded the first treaty between Parthia and Rome. Finally, in southern Iran the new dynasty of the Sāsānians, under the leadership of Ardashir I (reigned 224–241), overthrew the Parthian princes, ending the history of Parthia.

A rock carved relief of Mithridates I of Parthia (r. c. 171–138 BC), at Khong-e Azhdar, city of Izeh, Khuzestan Province

The Sāsānian Period

Sāsānian dynasty, ancient Iranian dynasty evolved by Ardashīr I in years of conquest, AD 208–224, and destroyed by the Arabs during the years 637–651. The dynasty was named after Sāsān, an ancestor of Ardashīr I. For a period of more than 400 years, Iran was once again one of the leading powers in the world, alongside its neighboring rival, the Roman and then Byzantine Empires. Most of the Sassanian Empire’s lifespan was overshadowed by the frequency of the all-comprising Roman–Persian Wars; the last was the longest-lasting conflict in human history. In fact, it started in the first century BC by their predecessors, the Parthians and Romans, the last Roman–Persian War was taken place in the seventh century. The Persians defeated the Romans at the Battle of Edessa in 260 and held the emperor Valerian as a hostage for the reminder of his life. The Sasanian era, encompassing the length of the Late Antiquity, is considered to be one of the most important and influential historical periods in Iran, and had a major impact on the world. In many ways the Sassanian period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization, and constitutes the last great Iranian Empire before accepting Islam. Persia influenced on Roman civilization considerably during Sassanian times, their cultural influence extending far beyond the empire’s territorial borders, reaching as far as Western Europe, Africa, China and India and also playing a prominent role in the formation of both European and Asiatic medieval art. This influence carried forward to the Muslim world. The dynasty’s unique and aristocratic culture transformed the Islamic conquest and destruction of Iran into a Persian Renaissance. Much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing, and other contributions to civilization, were taken from the Sassanian Persians into the broader Muslim world.

Ahura Mazda and Ardashir I

Rock-face relief at Naqsh-e Rustam of Persian emperor Shapur I capturing Roman emperor Valerian and Philip the Arab

Islamic conquest of Persia

One of the first transformations the Abbasids made after taking power from the Umayyads was to move the empire’s capital from Damascus, in the Levant, to Iraq. The latter region was influenced by Persian history and culture, and moving the capital was part of the iranian demand for Arab influence in the empire. The city of Baghdad was constructed on the Tigris River, in 762, to serve as the new Abbasid capital. As the power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, a series of dynasties rose in various parts of Iran, some with considerable influence and power. Among the most important of these overlapping dynasties were the Tahirids in Khorasan (821–873); the Saffarids in Sistan (861–1003, their rule lasted as maliks of Sistan until 1537); and the Samanids (819–1005), originally at Bukhara. The Samanids eventually ruled in an area from central Iran to Pakistan. By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control to the growing Persian faction known as the Buyid dynasty (934–1062). Since much of the Abbasid administration had been Persian anyway, the Buyids were quietly able to assume real power in Baghdad. The Buyids were defeated in the mid-11th century by the Seljuq Turks, who continued to exert influence over the Abbasids, while publicly pledging allegiance to them. The balance of power in Baghdad remained as such – with the Abbasids in power in name only – until the Mongol invasion of 1258 sacked the city and definitively ended the Abbasid dynasty.

The Abbasid Caliphate, Iranian semi-independent governments and Persianate states

One of the first changes the Abbasids made after taking power from the Umayyads was to move the empire’s capital from Damascus, in the Levant, to Iraq. The latter region was influenced by Persian history and culture, and moving the capital was part of the Persian mawali demand for Arab influence in the empire. The city of Baghdad was constructed on the Tigris River, in 762, to serve as the new Abbasid capital. As the power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, a series of dynasties rose in various parts of Iran, some with considerable influence and power. Among the most important of these overlapping dynasties were the Tahirids in Khorasan (821–873); the Saffarids in Sistan (861–1003, their rule lasted as maliks of Sistan until 1537); and the Samanids (819–1005), originally at Bukhara. The Samanids eventually ruled an area from central Iran to Pakistan. By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control to the growing Persian faction known as the Buyid dynasty (934–1062). Since much of the Abbasid administration had been Persian anyway, the Buyids were quietly able to assume real power in Baghdad. The Buyids were defeated in the mid-11th century by the Seljuq Turks, who continued to exert influence over the Abbasids, while publicly pledging allegiance to them. The balance of power in Baghdad remained as such – with the Abbasids in power in name only – until the Mongol invasion of 1258 sacked the city and definitively ended the Abbasid dynasty.

Interior view of the Nizam al-Mulk and Malik Shah tomb, Isfahan

Mongol conquest and Ilkhanate

Misunderstanding of how essentially fragile Sultan Alā al Dīn Moḥammad Khārazm Shah’s apparently imposing empire was, its distance away from the Mongols’ eastern homelands, and the strangeness of new terrain all doubtless induced fear in the Mongols, and this might partly account for the terrible events with which Genghis Khan’s name has ever since been associated. During 1220–21 Bukhara, Samarkand, Herāt, Tus, and Neyshābūr were razed, and the whole populations were slaughtered. The Khwārezm Shah fled, to die on an island off the Caspian coast. His son Jalāl al-Dīn survived until he was murdered in Kurdistan in 1231.However, he failed to unite the Iranian regions, even though Genghis Khan had withdrawn to Mongolia, where he died in August 1227. Iran was left divided, with Mongol agents remaining in some districts and local adventurers profiting from the lack of order in others. A second Mongol invasion began when Genghis Khan’s grandson Hülegü Khan crossed the Oxus in 1256 and demolished the Assassin fortress at Alamūt. In 1258 Hülegü besieged Baghdad. Al-Mustasim, the last Abbāsid caliph of Baghdad, was trampled to death by mounted troops, and eastern Islam fell to pagan rulers. Il-Khanid military emirs began to establish themselves as independent regional potentates after 1335. At first, two of them, who were formerly military chiefs in the IlKhans’ service, competed for power in western Iran, ostensibly acting on behalf of rival Il-Khanid puppet princes. Thus in 1353 Shīrāz became the Muzaffarid dynasty’s capital, which it remained until conquest by Timur in 1393. The ruling Timurid dynasty, or Timurids, lost most of Persia to the Aq Qoyunlu confederation in 1467, but members of the dynasty continued to rule smaller states, sometimes known as Timurid emirates, in Central Asia and parts of India. In the 16th century, Babur, a Timurid prince from Ferghana (modern Uzbekistan), invaded Kabulistan (modern Afghanistan) and established a small kingdom there, and from there 20 years later he invaded India to establish the Mughal Empire. Members of the Timurid dynasty were strongly influenced by the Persian culture and established two significant empires in history, the Timurid Empire (1370–1507) based in Persia and Central Asia and the Mughal Empire (1526–1857) based on the Indian subcontinent.

Jalal al-Din Khwarazm Shah crossing the rapid Indus River, escaping Genghis Khan and the Mongol army.

Stucco mihrab commissioned in1310 by Mongol ruler Oljaytu in Jameh Mosque of Isfahan.

The Turkmens

From the end of the reign of the Ilkhanate in Iran, Turkoman tribes came to Western Asia from the vicinity of Kharazm and around the Aral Lake and the east of the Caspian Sea during the Mongol campaigns and settled in the northwest of Iran. They gradually gained strength and took advantage of the period that occurred after the fall of the Ilkhans, and started raiding the surrounding areas and capturing the cities. After Timur’s death, two competing Turkmen clans had established an emirate in Azerbaijan and Diyarbakir, one of them was called Qara Qyunlu or Black Sheep and the other was called Agh Qyunlu or White Sheep and they were each other’s blood enemies. They were present in Iran’s political arena for about a century.

The Safavids

Safavid dynasty, ruling dynasty of Iran whose establishment of Shiite Islam as the state religion of Iran was a major factor in the emergence of a unified national consciousness among the various ethnic and linguistic elements of the country. The Safavids were descended from Sheykh Safi al-Din (1253–1334) of Ardabil, head of the Sufi order of Safaviyeh. The founder of the dynasty, Ismāil I, as head of the Sufis of Ardabīl, enable to capture Tabrīz from the Aq Koyunlu , and in July 1501 Ismāil was enthroned as shah, although his area of control was initially limited to Azerbaijan. In the next 10 years he subjugated the greater part of Iran and annexed the Iraqi provinces of Baghdad and Mosul. Despite the predominantly Sunni character of this territory, he proclaimed Shīʿism the state religion. In 1588 Abbās I was brought to the throne. Realizing the limits of his military strength, Abbās made peace with the Ottomans on unfavourable terms in 1590 and directed his onslaughts against the Uzbeks. With his new army, Abbās defeated the Turks in 1603, forcing them to relinquish all the territory they had seized, and captured Baghdad. He also expelled (1622) the Portuguese traders who had seized the island of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf early in the 16th century. Shah Abbās’s remarkable reign, with its striking military successes and efficient administrative system, raised Iran to the status of a great power. Trade with the West and industry expanded, communications improved. The capital, Esfahān, became the centre of Safavid architectural achievement, manifestation . After the death of Shah ʿAbbās I (1629), the Ṣafavid dynasty lasted for about a century, but, except for an interlude during the reign of Shah ʿAbbās II (1642–66), it was a period of decline. Isfahan was besieged by the Afghan forces led by Mahmud Hotaki after their decisive victory over the Safavid army at the battle of Gulnabad, close to Isfahan, on 8 March 1722. After the battle, the Safavid forces fell back in disarray to Isfahan. The famine soon prevailed and the shah capitulated on 23 October, abdicating in favor of Mahmud, who triumphantly entered the city on 25 October 1722.

The Battle of Chaldiran between Iran & Ottoman at the 40 Sotoun Palace in Isfahan. 1514

Abbas the Great portrait from Italian painter

Afsharid

Iran’s territorial integrity was restored by a native Iranian Afshar warlord from Khorasan, Nader Shah. He defeated and banished the Afghans, defeated the Ottomans, reinstalled the Safavids on the throne, and negotiated Russian withdrawal from Iran’s Caucasian territories, by the Treaty of Resht and Treaty of Ganja. By 1736, Nader had become so powerful he was able to depose the Safavids and have himself crowned shah. In 1739 he invaded Mughal India and bringing back immense wealth to Persia. n his way back, he also conquered all Uzbek khanates –except Kokand –and made the Uzbeks his vassals. He also firmly reestablished Persian rule over the entire Caucasus, Bahrain, as well as large parts of Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Nader was assassinated in 1747.

Statue of Nader Shah at the Naderi Museum in Mashhad

The Zand dynasty

Following the death of the Nāder Shāh, Karim Khān Zand became one of the major contenders for power. By 1750 he had sufficiently consolidated his power. Karīm Khān never claimed the title of shāhanshāh (“king of kings) and, with 30 years of benevolent rule, gave southern Iran a much needed respite from continual warfare. He encouraged agriculture and entered into trade relations with Great Britain. His death in 1779 was followed by internal dissensions and disputes over successions. Between 1779 and 1789 five Zand kings ruled briefly. In 1789 Lotf Ali Khān proclaimed himself as the new Zand king and took energetic action to put down a rebellion led by Āghā Moḥammad Khān Qājār that had begun at Karīm Khān’s death. Outnumbered by the superior Qājār forces, Loṭf Ali Khān was finally defeated and captured at Kermān in 1794. His defeat marked the final eclipse of the Zand dynasty, which was supplanted by that of the Qājārs.

Karim Khan Castle, The royal residence of the Zand dynasty. Shiraz

The Qajar dynasty

In 1779, Agha Moḥammad Khan, a leader of the Turkmen Qajar tribe, set out to reunify Iran. By 1794 he had eliminated all his rivals, and In 1796 he was formally crowned as shah, or emperor. Agha Moḥammad was assassinated in 1797 and was succeeded by his nephew, Fathalī Shāh. he attempted to maintain Iran’s sovereignty over its new territories, but he was disastrously defeated by Russia in two wars (1813, 1828) and thus lost Georgia, Armenia, and northern Azerbaijan. Fatḥalī’s reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. When Moḥammad Shāh died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Nāṣer od-Dīn (reigned 1848–96), who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qājār sovereigns. During his reign Western science, technology, and educational methods were introduced into Iran and the country’s modernization was begun. When Nāṣer was assassinated by a fanatic in 1896, the crown passed to his son Moẓaffar od-Dīn Shāh (reigned 1896–1907), a weak and incompetent ruler who was forced in 1906 to grant a constitution that called for some curtailment of monarchial power. His son Moḥammad Alī Shāh (reigned 1907–09), with the aid of Russia, attempted to rescind the constitution and abolish parliamentary government. In so doing he aroused such opposition that he was deposed in 1909, the throne being taken by his son. Aḥmad Shāh (reigned 1909–25), who succeeded to the throne at age 11 With a coup d’etat in February 1921, Reza Khan (ruled as Reza Shah Pahlavi, 1925–41) became the preeminent political personality in Iran; Ahmad Shah was formally deposed by the majlis (national consultative assembly) in October 1925 while he was absent in Europe, and that assembly declared the rule of the Qajar dynasty to be terminated.

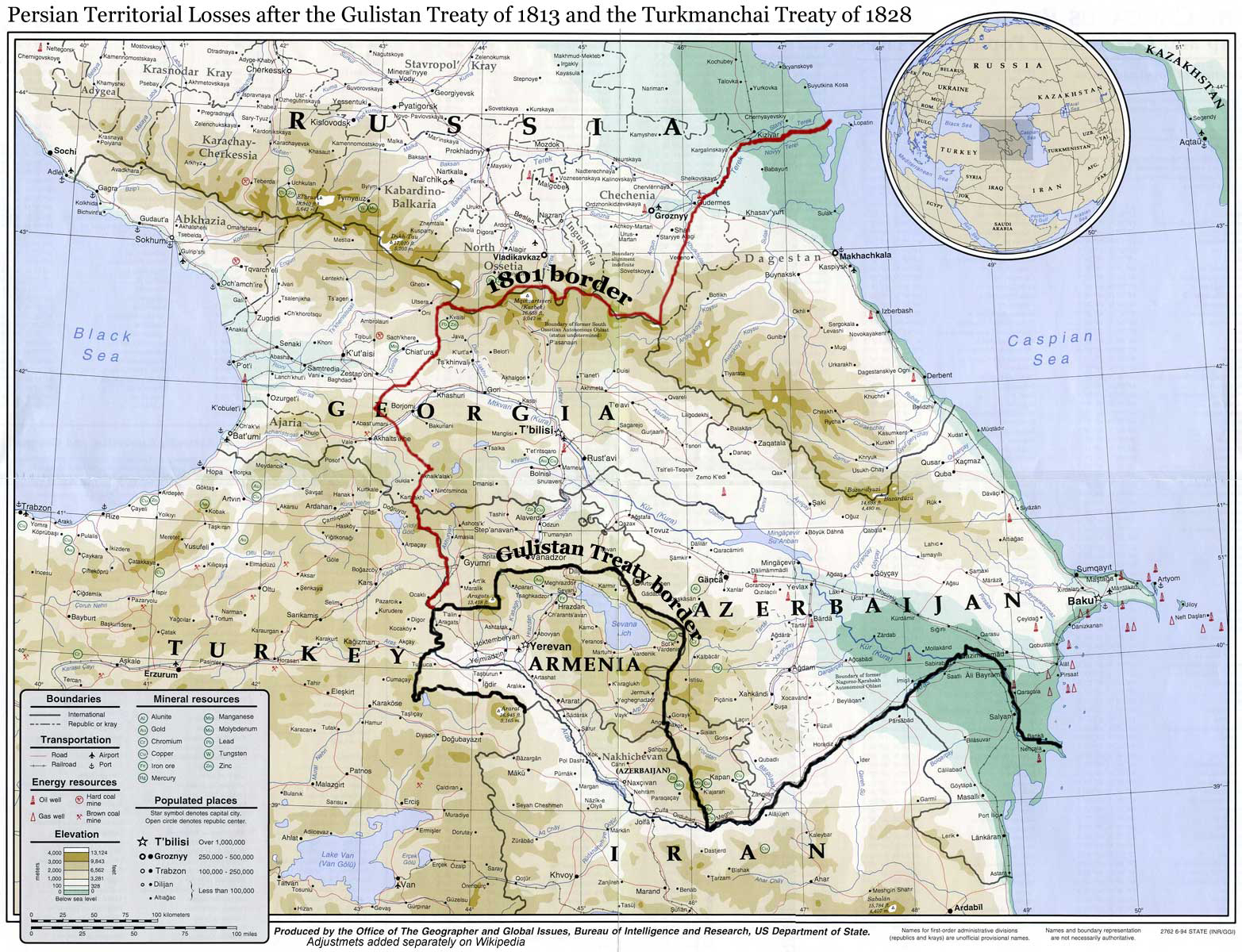

Northwestern Iran’s borders before and after Russo-Persian War. 1804-1813& 1826-1828

Edward VII – Nasser-ed-Din Shah – Alexandra of Denmark. London 1889

The Pahlavi dynasty

Reza Shah

In collaboration with a political writer, Ziyaaldin Tabatabai, Reza Khan staged a coup in 1921 and took control of all military forces in Iran. Between 1921 and 1925 Reza Khan-first as war minister and later as prime minister under Ahmad Shah—built an army that was loyal solely to him. He also managed to forge political order in a country that for years had known nothing but turmoil.He deposed the weak Ahmad Shah in 1925 and had himself crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi. During the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, educational and judicial reforms were effected that laid the basis of a modern state and reduced the influence of the religious classes. the status of women improved. The custom of women wearing veils was banned, the minimum age for marriage was raised, and strict religious divorce laws (which invariably favoured the husband) were made more equitable. The number and availability of secular schools increased for both boys and girls, and the University of Tehran was established in 1934. His refusal to abandon what he considered to be obligations to numerous Germans in Iran served as a pretext for an Anglo Soviet invasion of his country in 1941. Intent on ensuring the safe passage of U.S. war matériel to the Soviet Union through Iran, the Allies forced Reza Shah to abdicate, placing his young son Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi on the throne.

Ahmad Shah and Reza Khan after 1921 Persian coup

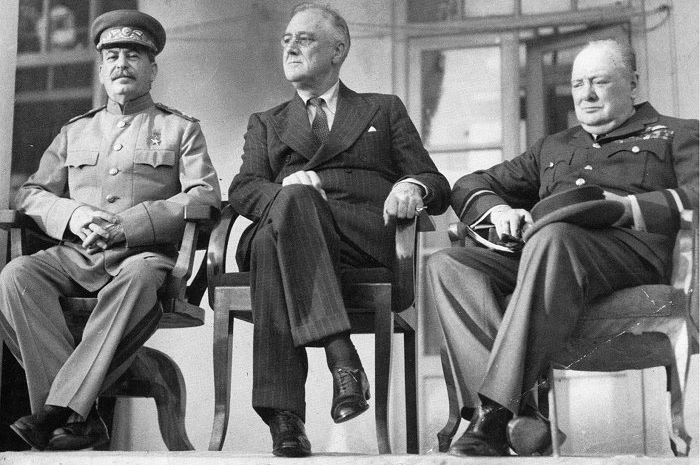

The Tehran Conference: Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. 1945

Mohammad Reza Shah

Mohammad Reza Shah succeeded to the throne in a country occupied by foreign powers, crippled by wartime inflation, and politically fragmented. Following the war, a loose coalition of nationalists, clerics, and noncommunist left-wing parties, known as the National Front, coalesced under Mohammad Mosaddeq, a career politician and lawyer who wished to reduce the powers of the monarchy and the clergy in Iran, and, when Mosaddeq became prime minister in 1951, he immediately nationalized the country’s oil industry. In August 1953, following a round of political skirmishing, Mosaddeq’s quarrels with the shah came to a head, and the Iranian monarch fled the country. Almost immediately, despite still-strong public support, the Mosaddeq government buckled during a coup funded by the CIA. In 1961 the shah dissolved the 20th Parliament and cleared the way for the land reform law of 1962. The land reforms were a mere prelude to the shah’s “White Revolution,” a far more ambitious program of social, political, and economic reform. Put to a plebiscite and ratified in 1963, The new policies of the shah did not go unopposed, however; many Shīʿite leaders criticized the White Revolution, holding that liberalization laws concerning women were against Islamic values. he shah’s reforms also had failed completely to provide any degree of political participation. Traditional parties such as the National Front had been marginalized, while others, such as the Tudeh Party, were outlawed and forced to operate covertly. In this environment, members of the National Front, the Tudeh Party, and their various splinter groups now joined the ulama in a broad opposition to the shah’s regime. Ayatollah Khomeini had continued to preach in exile about the evils of the Pahlavi regime, accusing the shah of irreligion and subservience to foreign powers. In January 1978, incensed by what they considered to be slanderous remarks made against ayatollah Khomeini in a Tehran newspaper, thousands of young madrasah students took to the streets. T The shah, weakened by cancer and stunned by the sudden outpouring of hostility against him, vacillated, assuming the protests to be part of an international conspiracy against him. Many people were killed by government forces in the ensuing chaos. In January 1979, in what was officially described as a “vacation,” Shah and his family fled Iran; he died the following year in Cairo. On February 11, the country’s armed forces declared their neutrality, effectively ending the shah’s regime.

The Iranian delegation to the ICJ in 1953 for Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. case (Prime Minister Mossadegh in center)

One of the images of the Iranian Revolution in 1978-79

Islamic republic

The Iran-Iraq War (1980–88)

In September 1980 a long-standing border dispute served as a pretext for Iraqi Pres Saddam Hussein to launch an invasion of Iran. Iran’s formidable armed forces had played an important role in ensuring regional stability under the shah but had virtually dissolved after the collapse of the monarch’s regime. The weakened military proved to be unexpectedly resilient in the face of the Iraqi assault, however, and, despite initial losses, achieved remarkable defensive success. but the war soon lapsed into stalemate and attrition. In addition, its length caused anxiety among the Arab states and the international community because it posed a potential threat to the oil-producing countries of the Persian Gulf. Finally, ayatollah Khomeini announced Iran’s acceptance of a UN resolution that required both sides to withdraw to their respective borders and observe a cease-fire, which came into force in August 1988.

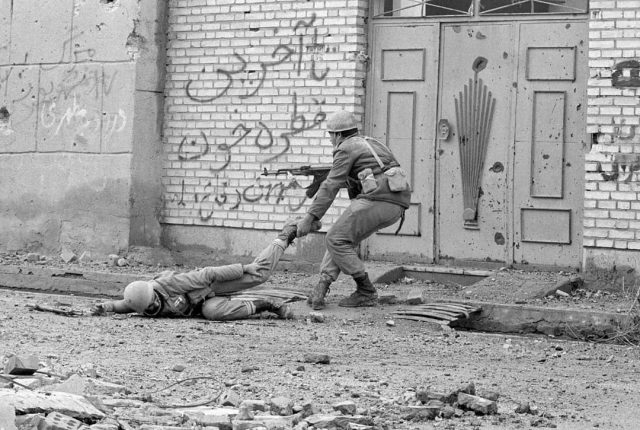

An Iranian soldier rescuing a wounded soldier. The Persian graffiti on the wall reads as “will defend the motherland until the last drop of blood”. Battle of Khorramshahr- 1980

An Iranian soldier rescuing a wounded soldier. The Persian graffiti on the wall reads as “will defend the motherland until the last drop of blood”. Battle of Khorramshahr- 1980